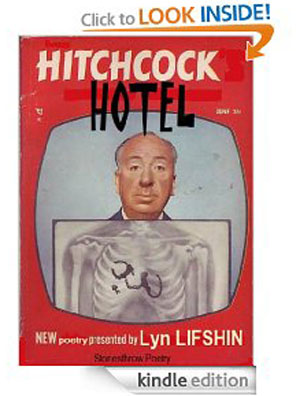

Hitchcock Hotel

Hitchcock Hotel

An e-book for Kindle users

by

Lyn Lifshin

e-book available from Amazon.com

235 pages

$7.77 e-book price

$0.00 to Kindle Prime Users (borrow for free on your Kindle)

Poetry about Alfred Hitchcock

Review by Victor Schwartzman

Target Audience Poetry Editor

Just available now comes Lyn Lifshin’s Hitchcock Hotel, from Stonesthrow Poetry (available via Amazon.com, as a Kindle e-book). Alfred Hitchcock is the director most associated with things creepy, and Halloween is the most frightening day on the calendar until Election Day!

Lifshin has not written a series of poems about Hitchcock’s films. That would be a yawn. Instead, the poems are about Hitchcock and his problematic personality. And that makes this book of poems unique.

Sir Alfred died worrying that he had become irrelevant to modern audiences. 1970’s audiences and later ones often found his films the opposite of frightening. The ‘master of the macabre’ (or was that William Castle?) actually made only a film and a half to earn him horror movie status: Psycho and parts of The Birds and Frenzy.

The rest of Hitchcock’s films are suspense films, not horror or even frightening. However, it turns out his personality was frightening.

Hitchcock made Psycho partly because he was worried about becoming irrelevant. The audience wanted violence and being frightened? He decided to give it to them, in spades! And, by the time it came out, audiences were ready for a major switch in the pacing of thrillers and how much violence they saw onscreen.

Hitchcock’s films remain interesting for many reasons, among them how they reflect creepy aspects of his personality. A recent HBO film explored Tippi Hedren’s abuse problems with Hitchcock on The Birds and Marnie, depicting him as a stalker, demanding sex from her and destroying her career when she refused. An upcoming theatrical film, starring Anthony Hopkins, apparently is about Hitchcock’s insecurities leading up to Psycho.

Lyn Lifshin, who has written more books of poetry than most libraries own, takes on Hitchcock in her new collection, available in the Kindle format. Lifshin has periodically written books built around central themes. Barbaro: Beyond Brokenness, about a race horse, is probably the best known. A recent book, Tango, Knife Edge & Absinthe (out from Night Ballet Press, and to be reviewed here soon) is a series of poems built around the Tango.

Building a series of poems about Hitchcock, Lifshin did not simply watch the movies. This poet did research! The poems contain details of interviews with Hitchcock, various bits from his life, and some poems about his rarely mentioned wife, Alma. Lifshin seems to KNOW the guy.

So here is one artist, a poet with her words, assessing the personality of another artist, a poet with his films. She is tall and blonde and dances ballet; he, as Tippi Hedren has claimed, was so fat and ugly he had to blackmail women into sex. Lifshin is a very strong woman, Hitchcock loved in real life controlling women.

Expect fireworks from these poems.

So what do we get? First, the recognition that Hitchcock’s films resemble in eerie ways his personality and life (just as a poet’s work resembles hers). That a creepy guy made creepy movies ain’t hard to believe.

AS IF THERE WAS A HUGE

stewing pot of images

deep inside Hitchcock

bubbling to the surface

mysterious, terrifying,

wild gems from Hitch’s

own secret longings

and imagination, dream

like images never quite

logical but wild as

long hair under water.

All he couldn’t deal

with with women

bloomed in rich

tapestries in the work

tho it left him lonely

and scattered but the

private desire, the

half remembered

scenes bloomed into

art that scared and

delighted so many

Not Mr. Nice Guy. .

Reflected within Hitchcock’s films are his obsessions with women, especially focusing on cool blondes with fire inside. Dial M for Murder has been characterized as Hitchcock reflecting himself through the murderer, noting the character played by Ray Milland directs the murderer on how he wants his wife killed. How many films reflect aspects of his personality? All of them. That is why a Hitchcock film is a Hitchcock film, duh. How many of the films reflect stories from his own life, are allegories about his experiences and desires? Probably, in the central plots, all of the films Hitchcock made on his own, starting with Rope. As Lifshin notes, Hitchcock shifted plots to reflect his own experiences, becoming more and more extreme as he went on, leading to Frenzy, which features a ghastly explicit rape/murder sequence which forces the viewer to become a voyeur far more than Hitchcock’s other films had. Frenzy is both Hitchcock’s most “modern” film and his most revolting.

One of Hitchcock’s favourite approaches is to find fear in the disruption of the expected. In The Birds he found a perfect allegory—birds, for no given reason, break the usual chirping routine and instead begin attacking humans. There is no explanation for why the attacks begin and no idea when they will end. No safe place exists, no refuge is possible: outside is deadly, but being inside is not much better. Several of Lifshin’s poems are about that film:

WHEN THE JUNGLE GYM FILLS WITH BLACK BIRDS

When black birds dot

the bars, first one, then

another four. Black

rhinestones glistening

and ebony swooping,

startling. When the

bars became a cage of

fear and the birds

grow increasingly

agitated. When the

birds suddenly take off,

swarm, cast licorice

shadows and then

swoop to attack, shatter

the eye glasses of

one girl, it is sure

nothing that seemed

to be safe won’t

be changed

The Birds was Hitchcock’s last great film. The glory days were behind him. His techniques were indeed outdated for audiences brought up on receiving a ‘bump’ every few minutes, first introduced by the James Bond film Dr. No. Hitchcock was happy with three or four major suspense sequences in an entire film, but Dr. No gave audiences major sequences every three or four minutes. The pacing was much faster, and what followed for Hitchcock was increasing decreasing results, as it were. Marnie, Topaz, Torn Curtain, Family Plot—only cinephiles who have not seen these films describe them as masterpieces.

Hitchcock knew this, and in his later years rested on laurels which were lost on a younger audience. See how Lifshin describes a rare public interview Hitchcock gave:

ALFRED HITCHCOCK IS INTERVIEWED ON JAMES LIPTON’S ACTOR’S STUDIO

He’s reluctant, in a way,

prefers few words in

public. “Thanks” for a

life time achievement

award or walk on parts

in a film where he’s

barely noticed. He could

tell James about his

childhood ordeals, the

mysterious night locked

in a police cell for

no reason. The applause,

ok, that’s par but will

he have to say much

about the blondes he

can’t stand being taunted

by? Some of the guests

sing or do a little soft

shoe. Hitchcock knows

he’ll be lucky to get

across the stage, wants

to get behind a table

to not show how large

he is. He knows he can

put on a front, use the

clash between reality

and illusion to draw

the audience in then

throw them off. He

knows his reputation

blinds them, leaves them

fumbling in the dark for

all the questions they ask.

They won’t truly see him

anymore than if their

eyes were glazed, their

cracked eye glasses

shattered

Take the poem in the larger context. It’s all about the aging artist basking in the dying glow of fading work. It is easy to believe that this image of Hitchcock is quite true—in many respects he was going through the motions after Marnie. His films came farther apart, and increasingly appeared to reflect past glories. Frenzy feels desperate to attract an audience.

HE WAS OBSESSED WITH MONEY

as if it was power, a mask

to camouflage his awkwardness.

He had paintings, cattle ranches.

He grew richer every year but

he seemed sad, as if whatever

he had wasn’t enough. He was

like a schoolboy who never

grew up. Obsessed with sex like

a young boy he had endless

dirty jokes, vulgar stories. They

amused him more than anyone

else. But it was like money,

power over the women, a way

to surprise them, have their

attention, control them like

jumping on a woman in a night

gown in a bed on the set. He

was not what he wanted to be,

not handsome or suave and he

never came to terms with

what he was

It is entirely possible to conclude at this point that Ms. Lifshin does not think a huge amount of Sir Alfred as a person, good fellow or gentleman.

FANTASY VOYEUR

as if sure everyone

else was doing something

dark and forbidden,

kinky sex and loving it,

as if something in him

was not up to it,

never was, he’d blurt

out blue passages,

suggest a gin and

menstrual blood drink,

whisper something that

would titillate a blonde

beauty, get a rise from her

in the one way he could

There was one strong woman in Hitchcock’s life—his life partner, and film-making partner. Lifshin writes about her and what she faced in life as Hitchcock’s wife:

ALMA

with her dark cloche hat half over her eyes

and her short brown hair, glasses, a smile that

went from slightly turned up to a down

at the corners curl, a grimace. Years later

would she still have asked him to marry?

Lively and smart, not a blonde beauty but

full of ideas, would she have traded the

wealth, the travel the excitement for maybe

one night of sex? After a few years,

that bulge of flesh moving into her

briefly and then, like a barricade at the

other end of the table, just enough to make

the daughter she’d make a life of as

she helped Alfred with film negotiations

while he watched every hair on some blonde

beauty, hardly looked at her except as a

mother, an assistant. She heard his sex talk

to the babes knowing he’d never touch her.

She helped him edit trick shots of those

mechanical birds, animation because he

needed her even tho he didn’t want her as a

husband, a man and she soothed and apologized

the distraught women when he embarrassed

them, told them she was sorry they had to go

thru this, over and over as she must have told herself

Lifshin, as always, writes clearly, crisply. Her assessment of Hitchcock is honest and as direct as can be. In the end, does she think Hitchcock learned anything about himself before he died? As one last thought, quite suitable for Halloween:

HITCH WRITES TO TIPPI FROM THE GRAVE

under the tangle of roots and leaves,

past champagne to dull the aloneness,

red wine. Under pale bulbs, color

of the silence, fleshly as his belly

was before, smooth as her breasts

under red lambs wool. A lamb

herself, one he was sure he could

take and cuddle, keep from predators.

Sure, he thinks, he should apologize

for a few things: that the birds were

real. Sure he knew but it was for

those perfect frames of fear. The

terror he’d never catch any other way.

He wonders if she hates him for that,

thinks maybe he should write her.

Yes, he admits, he said some off color

things, maybe he moved in too abruptly

but what is a lonely slob of a man

going to do? Grace Kelly forgave him and

Ingrid Bergman. He thinks Tippi had such

promise, such looks. What’s a dirty joke

he wants to tell her: we’re all going to

die. Earth molds around his bones

like lava tubes around what had been

living, caught in molten flame as he

wants to tell Tippi he felt some afternoons,

how isolated hours were without the

camera. It was never good he knows the

last times they saw each other. Even

Alma couldn’t soothe things over. But

to see her no longer, as the blonde beauty

he longed for might be worse than to

never see her again.

![]() A review from Amazon customer:

A review from Amazon customer:

In Hitchcock Hotel, Lyn draws in Alma, his "drab" wife "on the sidelines" contrasting his "lovelies" all obsessively-blonde in his movies. "Birds are eerie music" to his loneliness as Lyn pecks apart his life in this stunning group of poems, each more intense than the last. Hitchcock is caged, except thru the lens of his camera where he is in control. He makes the blondes suffer as depicted in Lyn's poems as she points the lens at him with her pen. Interesting and a great read.